A Beginner's Guide to the Command Line

This guide introduces the command line for developers who have only used desktop tools or are just starting out. This guide aims to help you understand how to control your computer through typed commands.

Before you begin, make sure you've the following:

- A computer running macOS, Windows, or Linux

- Access to your operating system's terminal application:

- macOS: Terminal (in Applications > Utilities)

- Windows 10 or later: Windows Terminal or Command Prompt

- Linux: Terminal (name and location varies by distribution)

- A Twilio account (sign up for a free Twilio trial account) to run the sample script

Info

You don't need any prior command line experience to use this guide.

Understand the evolution from typed commands to graphical interfaces and why the command line remains relevant:

Back in the dim and distant past, people controlled computers with typed commands. Then the Graphical User Interface (GUI) evolved and pointing and clicking superseded typing. That's how most people work with computers today, though often they use a finger on a touchscreen rather than a mouse on a desk.

You can still control computers by entering commands on the keyboard and, as you'll have guessed, this takes place at the command line. Windows, macOS and Linux all provide facilities for presenting you with a command line. These applications typically go by the names consoles or terminals.

On macOS, for example, the app is Terminal. You'll find it in Applications > Utilities. Different versions of Linux offer different terminal apps, and they typically call them Terminal and make them accessible from the desktop. Windows 10 has Windows Terminal; older versions have a Command Prompt entry in the Start menu which calls up their terminal app. Microsoft also has Windows Subsystem for Linux, which implements a Linux command line in Windows 10.

A terminal is just a presentation mechanism; the software doing the real work goes by the name "shell". That's why you might see PowerShell in your terminal window on a Windows PC. The shell provides the real interface between you and the computer; the terminal just displays the shell's output in a window and sends your key presses to the shell.

If you've used a Linux computer that someone configured not to start up a desktop screen, you've used the command line all along and communicated directly with a shell. You generally use terminal apps only from a GUI's desktop.

Experienced developers have favorite shells, but at the start, it's best to make use of the one your operating system provides. Once you understand how it works, and have begun making use of it, you can start to explore the alternatives.

Info

Throughout this guide, you'll see the terms "command line", "terminal", "console", and "shell" used somewhat interchangeably. While they technically refer to different parts of the system, they all relate to controlling your computer with typed commands.

Learn what the prompt is and how it signals the shell is ready for your input:

However, when you invoke a shell, you'll see what's known as a "prompt", the shell's cue to you to type in a command. When the command completes, you'll see the prompt appear again: the shell tells you that it's ready for its next task.

Many different shells exist, so you may not always see the same prompt when you use multiple machines. The most common Linux shell, Bash, uses the $ symbol as its standard prompt. macOS recently began using the Z Shell, which uses % as its prompt. On Windows, the prompt is usually a >. Whatever the symbol, and whatever information appears alongside it — often the current directory, but you might also see the drive letter, the name of the logged-in user, or the date — the prompt tells you the shell waits for input.

Current directory? This is another common term you'll read in discussions concerning the command line. You might also see people call it the "working directory". "Directory" is just shell-speak for the folder, "working" the one you're currently viewing in the terminal.

Discover how to navigate your file system using absolute and relative paths:

The sequence of directories containing a file or directory makes up its "path". Here's a macOS example:

/Users/Twilio/GitHub/scripts/imageprep.sh

This is an "absolute" path: it identifies precisely where you can find the file imageprep.sh. Linux and macOS use the /symbol, as shown above, to separate files and directories in the path, but Windows uses \ so just replace one with the other in this and the following examples if you're using Windows Terminal or PowerShell.

Depending on your shell, you may be able to use "relative" paths. Paths that depend on where you're starting from. These use the following markers:

.— the current directory...— a parent directory.

So if you're working in the directory /Users/Twilio/Documents/websource/ then you can access the script — the .sh file — mentioned above using the relative path:

../../GitHub/scripts/imageprep.sh

This means 'go up to the parent directory' (ie. Documents/), 'go up to the next parent directory' (Twilio/), then 'go down to GitHub/scripts/imageprep.sh'.

If you're wondering what the / right at the start of the first path is, it's special: it's the Linux and macOS "root" directory. This is the top-most directory from which all other branches.

You may see a ~ (tilde) in paths. It represents the current user's home directory, making it ideal for scripts used by different people.

To run the script imageprep.sh, you must provide its name at the prompt. If it's in a different directory from the one in which you're working, provide an absolute or relative path. If it's in the working directory, you can omit the path. However, you will need to tell the shell that the file is here: prefix it with ./ to indicate the current directory:

./imageprep.sh

Info

It's outside of the scope of this guide, but it's useful to know that Linux and macOS shells have a variable called $PATH that tells them where to look for files: it contains a list of directory paths. If you type just imageprep.sh, the shell will only look for the file in the directories included in $PATH. That's why you need the ./ above — /Users/Twilio/GitHub/scripts not listed in $PATH.

When referencing shell variables (though not when setting them), always prefix their names with the $ sign.

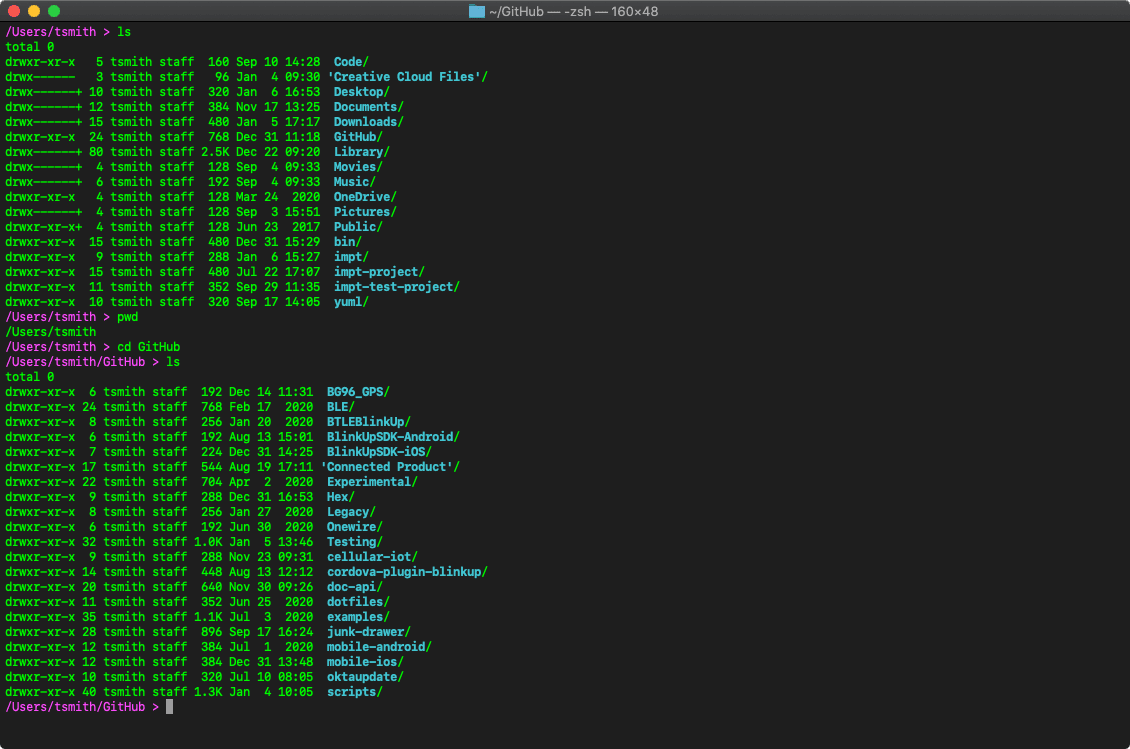

Explore essential commands for listing files, checking directories, and creating folders:

If you open up a terminal now, when the prompt appears enter one of the following commands:

| Platform | Command |

|---|---|

| macOS/Linux | ls |

| Windows Terminal | DIR |

These commands tell the shell to list the files and sub-directories within the current directory, also known as the working directory. How can you see what that is? With another command of course:

| Platform | Command |

|---|---|

| macOS/Linux | pwd |

| Windows Terminal | CHDIR |

To create a new directory, use the following command:

| Platform | Command |

|---|---|

| macOS/Linux/Windows Terminal | mkdir DIRECTORY_PATH |

If the value you put in place of DIRECTORY_PATH is just the new directory's name, the command creates it in the working directory.

To move or "change" to another directory, use the following commands:

| Platform | Command |

|---|---|

| macOS/Linux | cd DIRECTORY_PATH |

| Windows Terminal | CHDIR DIRECTORY_PATH |

There are literally dozens of commands you can enter, far too many to list here. There are lots of online resources that list them. Use your favorite search engine.

Learn how to provide additional information to commands using arguments, switches, and flags:

Most commands are more than a single word, you can provide extra information in the form of "arguments" placed after the command and separated by at least one space. Arguments might include target filenames or the location of the directory where the command's results will be placed.

The need to separate arguments with spaces means you need to take care with file and directory names that contain spaces. The technique of telling a shell to treat included spaces as part of an argument and not a separator goes by the name "quoting". For example, to stop the second space in the command

cat /Users/Twilio/my file.txt

from causing errors (specifically cat: /Users/Twilio/my: no such file or directory and cat: file.txt: no such file or directory), you wrap the argument in quotes:

cat "/Users/Twilio/my file.txt"

This correctly displays the contents of the named file.

Other arguments govern how the command works: these go by the names "switches", "flags" or "options" and have the prefix - or --. For example, you might issue the ls command mentioned above with these two switches:

ls -l -a

Respectively, these cause ls to output its list in columns (-l) and to include hidden files (-a). The ls command allows you to combine switches into a single statement:

ls -la

This has the same effect as the previous example but is more compact. Many commands work this way, but not all do. Many commands have the switches -h and/or --help which will cause them to output guidance — these will tell you if the command supports combining switches and flags this way.

Remember the mkdir command you saw earlier? If you provide a full path as an argument and that includes directories that don't exist, mkdir will display an error message. However, if you also include the -p switch, mkdir will also create any 'missing' directories within the path.

Learn how to automate tasks by combining commands with variables and logic:

The shell includes some commands, but many more run as standalone programs. Others are "shell scripts". Scripts make the command line attractive to developers because they combine multiple commands with variables and flow logic to automate key tasks.

For example, you might write a script to send SMS messages through the Twilio API. The script prompts for a phone number and message, confirms before sending, calls the API using curl, and parses the response to show success or failure.

Shell scripting opens up endless possibilities: extracting data points from log files, packaging apps for distribution, automating deployment processes, or interacting with any API. Scripts make these tasks repeatable, reliable, and fast.

Walk through a real-world script that sends an SMS message using the Twilio API:

This script demonstrates how you can automate API interactions from the command line. Here's the code:

1#!/bin/bash23# Twilio SMS Sender Script4# This script sends an SMS message using the Twilio API56# Set your Twilio credentials7TWILIO_ACCOUNT_SID="*YOUR_ACCOUNT_SID*"8TWILIO_AUTH_TOKEN="*YOUR_AUTH_TOKEN*"9TWILIO_PHONE_NUMBER="*YOUR_TWILIO_PHONE_NUMBER*"1011# Prompt for recipient phone number12echo "Enter the recipient's phone number (with country code, e.g., +1234567890):"13read TO_NUMBER1415# Prompt for message16echo "Enter your message:"17read MESSAGE_BODY1819# Confirm before sending20echo ""21echo "You're about to send:"22echo "To: $TO_NUMBER"23echo "Message: $MESSAGE_BODY"24echo ""25echo "Send this message? (y/n)"26read CONFIRM2728if [ "$CONFIRM" != "y" ]; then29echo "Message cancelled."30exit 031fi3233# Send the SMS using Twilio API34echo "Sending message..."35RESPONSE=$(curl -s -X POST "https://api.twilio.com/2010-04-01/Accounts/$TWILIO_ACCOUNT_SID/Messages.json" \36--data-urlencode "From=$TWILIO_PHONE_NUMBER" \37--data-urlencode "To=$TO_NUMBER" \38--data-urlencode "Body=$MESSAGE_BODY" \39-u "$TWILIO_ACCOUNT_SID:$TWILIO_AUTH_TOKEN")4041# Extract the message SID from the response42MESSAGE_SID=$(echo $RESPONSE | grep -o '"sid": *"[^"]*"' | head -1 | cut -d'"' -f4)4344if [ -n "$MESSAGE_SID" ]; then45echo "Message sent successfully!"46echo "Message SID: $MESSAGE_SID"47else48echo "Failed to send message. Response:"49echo $RESPONSE50fi

The shell reads and handles most lines in a script as if you'd keyed them in at the prompt. Lines beginning with # are comments — shells ignore any text after that symbol, up to the end of the line. The first line, #!/bin/bash, is special: it tells the operating system which program to use to run the script.

The script starts by defining three variables for your Twilio credentials. You need to replace the placeholder values (YOUR_ACCOUNT_SID, YOUR_AUTH_TOKEN, and YOUR_TWILIO_PHONE_NUMBER) with your actual credentials from the Twilio Console. Not including spaces on either side of the assignment operator, =, is a requirement in shell scripting.

The echo command prints text to the terminal, and read waits for you to type something and press Enter, storing what you typed in a variable. The script uses these commands to gather the recipient's phone number and message text.

Before sending, the script displays what you entered and asks for confirmation. The if statement checks whether you entered y to confirm. If you didn't, the script exits with an exit code of 0 (success) without sending anything.

To actually send the SMS, the script uses curl, a command-line tool for making HTTP requests. The -s flag makes curl run silently (no progress bar), -X POST specifies the HTTP method, and -u provides authentication credentials. The --data-urlencode flag safely formats each piece of data for the API. The $VARIABLE syntax reads the value of a variable you've defined.

The $(...) formatting tells the shell to run the code in the brackets and store whatever that code outputs in a variable. Here, you capture the entire API response in RESPONSE, then use grep and cut to extract just the message SID. This is a unique identifier Twilio assigns to each message.

Finally, the script checks if it successfully extracted a message SID. The -n flag in the if statement returns true if the variable contains any text. If the SID exists, you know the message was sent successfully.

To use this script, save it as send-sms.sh, then make it executable:

chmod +x send-sms.sh

Run it by entering ./send-sms.sh at the prompt.

Find additional resources to deepen your command line knowledge:

This guide has just scratched the surface of the command line, shells, and scripts. Hopefully, you now understand what these terms mean, and why developers make them key components of their toolkits. You may already be thinking about how you can do the same.

To learn more about specific commands, Linux and macOS provide a shell-accessible command called man which you provide a command as an argument. It will output the "manual" for the specified command — hence the name. Use the arrow keys to move up and down through the text, and hit Q to quit.

The Linux Documentation Project has a great guide to getting started with the Bash shell and a more detailed guide covering advanced scripting. There is also the Bash Manual.

For Mac users, there's an equivalent manual for the Z Shell. And Apple also has their own Terminal User Guide.

Microsoft has its own guides for Windows Terminal, PowerShell, and Windows Subsystem for Linux.

To explore more Twilio APIs from the command line, check out these quickstarts: